Advertising is Obsolete

Advertising is obsolete.

It is technological innovation, not consumer manipulation that will drive humanity towards a better future. You wanted flying cars, but got 140 characters for a reason: it was more comfortable for everyone involved. Companies didn’t have to invest in R&D, because they could convince customers to use inferior products through advertising. And consumers were too comfortable being fed cheap tech products where their attention and state of mind was being monetized. (Because as The Social Dilemma taught us, it’s not your data which is for sale at Facebook, it’s the subtle shift of your preferences that is being bought and sold).

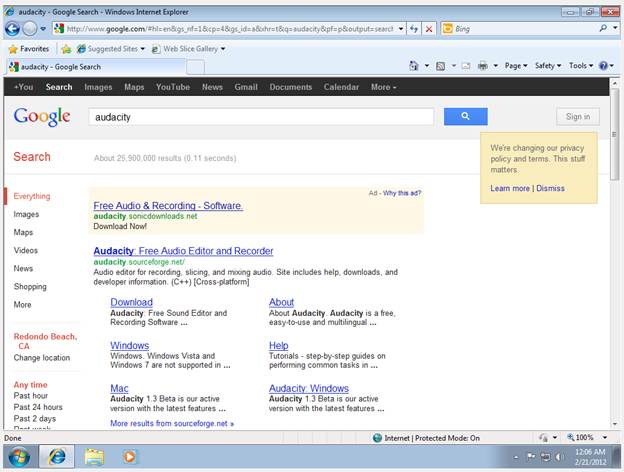

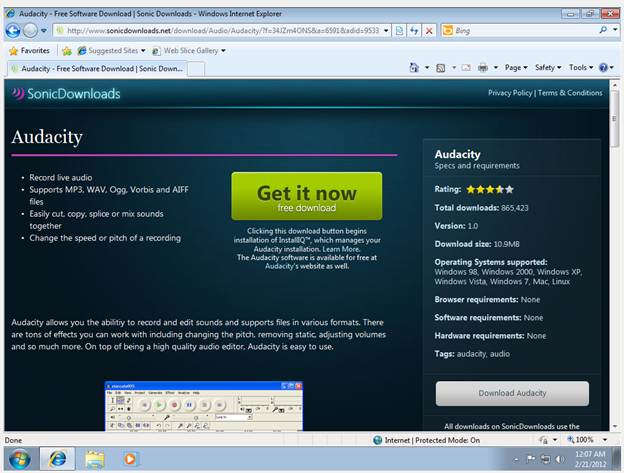

The Obsolescence of Advertising in the Information Age argues that in today’s information age, consumers can get all the information they need about the products and services they wish to purchase from the Internet, so advertising is no longer necessary. Advertising can only serve to persuade consumers to buy products not on their merits, but on their image. This serves to weaken market signals which would otherwise let the best products rise on their own.

Consider one market: video games. Is there a single game where the ad-supported version is better than the alternatives? Which game are people still going to be playing in 50 years: Stardew Valley, or Farmville? Easy answer: they already shutdown the original Farmville because people moved on.

I’ve seen this first-hand, when I coded games for several app stores. Early on, I missed the chance to get in early on the Apple App Store, or Google Play, but Microsoft eventually came around with Windows Phone. My friend and I wrote classic games, different variants of Solitaire, and a few experimental titles that all got decent downloads because there wasn’t anyone else focusing on Windows Phone at the time. We started making good money from our ad-supported games.

Of course, such a situation wasn’t going to last forever, and competitors started showing up. They knew how to hire teams to do the coding, QA, and graphics for a new game in China, while we did almost everything ourselves.

When we realized that our new livelihood was at risk, we knew we had to step up to the challenge. Our response to this was to start investing the money we were making from our ad-supported games into buying our own ads to promote our own titles.

At first, buying ads revolutionized our business. With each game that we released, we would heavily promote it in our own titles, and buy ads in other games to get even more users. This caused our apps to go up in the rankings, and get more natural downloads from people just visiting the app store home page. We made lots of money, and invested plenty back into out-advertising the competition.

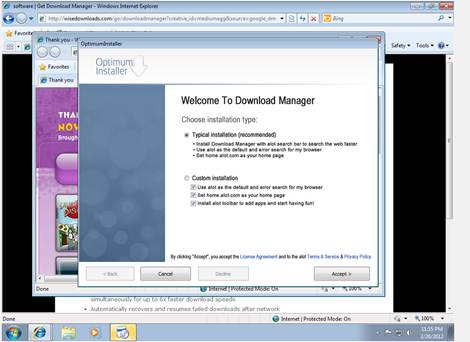

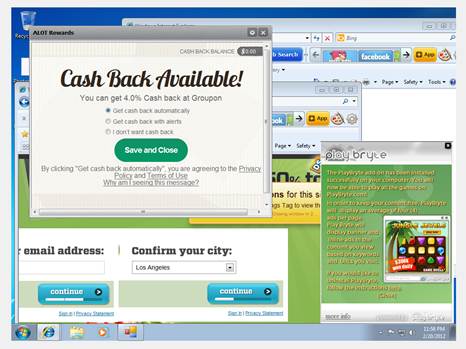

But then, our competitors caught on, and they were soon doing the same thing too. We were all just buying ads in each other’s games hoping to draw users to our own particular flavor of Solitaire. Long gone were the early days of fun and innovation. You had to make the games that would advertise well, and you had to use every trick in the book to retain the users you brought in.

Before we started advertising heavily, we tried out experimental titles, most of which failed on the marketplace, but at least they were innovative. As the business became more about advertising, we stopped all experimentation, and just focused on our core customers: the advertisers. Screw the users, it was the advertisers that paid us at the end of the day.

What was the point of this exercise? Did we manage to make a particularly innovative version of Solitaire for our users? We certainly had nice graphics and plenty of bells-and-whistles, but most of our optimizations were around user-retention and finding better ad-placements.

Eventually I got off this treadmill, but many things about it still bother me. We sold so many ad placements in our games, but what did that accomplish? How much did we shift our user’s opinions? In which directions, and on which topics? (We definitely showed plenty of election campaign ads for both sides) I have no idea, because the ad exchanges don’t expose that sort of information.

I’d like to see some platform ban advertising from their app store, and try out the policy proposed in The Obsolescence of Advertising in the Information Age . I predict we’d see more innovation, experimentation, and ultimately a stronger mutual respect between users and developers.